Text & Photos: Seb Carayol

Secrets, legends, and rumors often abound in the world of sound system building. Seb Carayol travelled to London in the late 2000s for a series of interviews with both legends and newcomers who keep the dances sounding nice.

Under his durag, reminiscent of an American rapper, Steppa Dan cuts an imposing shape. Leather clothing, golden tooth, partially-built spliff in one hand, he looks the part. You don’t joke with Steppa Dan even if the current situation jars with his vaguely menacing gait: he’s arranging tens of multicolored balloons on the ceiling. Tonight he’s celebrating his birthday and booked a mobile DJ of sorts for the occasion, Rory, from the Jamaican sound system Stone Love. Steppa can afford it, and it wouldn’t be right to ask how on this day of festivities… No flyer, no announcement but there’s little doubt he’ll fill the large snooker hall he rented in Norwood, where tables lay covered and a tattooed gentleman seemingly out of The Firm – Jocelynn Bain-Hoog’s book of portraits of local gangsters – offices as manager. Dan also has the system covered. For that he called on Shortman, one of the most renowned speaker builders in all the land. Over the years, word of mouth has mythologized builders like Shortman. There is the in-demand master Metro, with his coveted tube amps, the American immigrant Barracuda, the obsessively discreet Jah Tubby, who has never given an interview, the relatively new king of the pre-amps Mark “Mostec” Skeete.

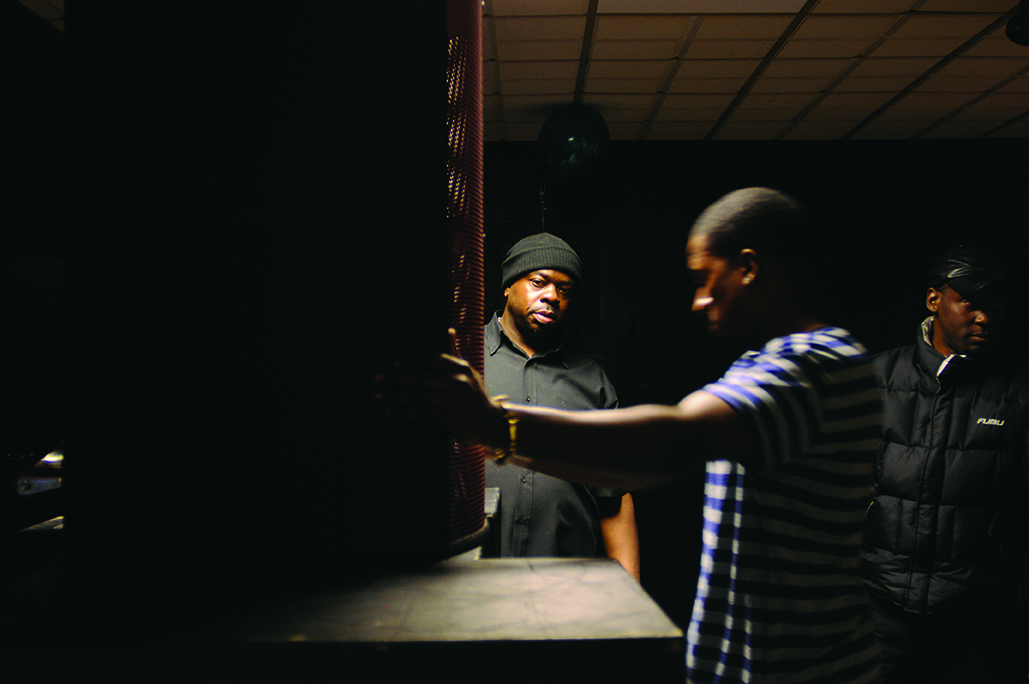

Shortman setting up at Norwood Snooker Club, 2008

On paper it’s relatively simple. To make a sound fit for UK crowds you need one turntable, Garrard 4HF for the purists, a pile of amplifiers, a few tons of speakers, and a pre-amp to control the show. Finding out just how all this gets built is just as simple. Phone calls abruptly ended due to unfounded rumors (“Metro is retired”) have led me to the furthest reaches of a rarely visited musical underground. For now, my search for answers begins here, in a Norwood snooker hall with Shortman, who is all smiles under his New York Yankees beanie. Steppa Dan? “A nice guy, I’ve known him for 20 years,” he says laughing. The network that connects builders to dances is what brought him here, and what brought him pretty much everywhere and helped build his formidable reputation.

Shortman had an advantage. His father, Charlie, was a carpenter and upholsterer. All a teenage Shortman had to do was steal his tools. His first attempt at building something was comical. “For the birthday of a friend in Brixton I build a big speaker without screws or glue, only nails. Halfway through the night it collapsed in the middle of the room!” The experience didn’t deter him though. The kid quickly learnt from his mistakes. Shortman practiced with local sound systems and quickly rose in notoriety, from Sir Higgins to the speakers of Frontline International. Over the years his list of client got longer, and the English scene began to resemble an arms race. Always bigger, always more powerful, especially with the advent of dub sound systems like Iration Steppas, Jah Tubbys or Aba Shanti in the ’90s. If the music is the message, you might as well cram it into the heads with a jackhammer. Today, King Earthquake can lay claim to the most ridiculous sound in England. At 400 to 600 Euro a speaker he’s not far from 100,000 Euros worth according to Shortman, who sees little profit from his “god-given” talent. As such, he’s had to recently relocate to a workshop much more modest than the one seen in the 2010 documentary Musically Mad. UK legislation is partly to blame, in particular an anti-noise law that continuously lowers the volume of working sound systems. Besides building, Shortman also rents his sound, with its bright red speakers reminiscent of a time when he painted cars, and is always ready to travel. Just this month, he sent a system to a Jamaican sound, Stereo Passion, and will travel on location to install it. He helped fellow Londoner Jah Marcus move to Ghana in style. This sonic carpenter smiles at the memory. “He has the biggest sound I’ve ever built, I sent 44 bass bins by boat!”

Shortman

Legislation or not, Shortman is at least able to export his know-how. Some of the elders in the building community like Metro haven’t been able to do the same. A mysterious character, this master of tube amps is the spiritual father of every English sound system engineer. His name inspired a generation of sound systems, starting with Metromedia. He is also one of the many enigmatic people that surround Jah Shaka, and the influence is clear. His voice and his habit of invoking “the gift of god” recall the way in which Shaka hosted his radio show on Kiss FM in the ’90s.

Finding Metro proves to be a real paper chase. Three hours of interview later and a story of destiny forms around the gangly figure of a soundman with the scars to prove it. At the end of the ’60s a shard of glass took out one of his eye during a fight at a party where he was selecting. He’s always had electronics in his blood. As with Shortman, it also runs in the family. As a young kid in Jamaica he realized that his cousin Tom was none other than Tom The Great Sebastian, one of the founding fathers of Jamaican sound systems. Fascinated by music he quit school at 14 to install Mercury radios, at a time when radios were more furniture than portable. What fascinated him most though were those “little glass bottles” inside. Tubes, well before transistors. He decided to satisfy his curiosity by taking apart and rebuilding amps and using an American electronics magazine that offered a build-it-yourself circuit.

Just as he began to enjoy himself he was sent to England to join his brother. The year was 1957 and in Jamaica sound systems were becoming a phenomenon. A young Metro arrived in a country that was well behind on this front, “With 27 discs given by Tom for my brother.” It was a cold awakening that ended up motivating him. His mission would be to build an amp worthy of those of Coxsone and Duke Reid. Where to begin? With some perseverance he discovered Voltection, a company that built amps for radio and communications and was only a bus ride away from London. It wasn’t bad for a first buy but not quite the kind of “bottom line” that would make you jump to the ceiling either.

The legendary builder Metro

After a few nights spent selecting in the basement of a bar managed by famous east London gangsters the Kray twins, using homemade speakers built from leftover wood found at his job, Metro felt he was ready. He’d listened to a lot of advice. He had a gift. He’d bought resistors, capacitors, and lamps for nothing on the pavements of Tottenham Court Road even though England was full of military surplus from the second World War. He was ready to operate. He broke his amp down piece by piece, soldered, added, improvised. A year after his arrival in this quiet land, the amplifier he’d rebuilt sounded better, and was more powerful, than the one his compatriot had just brought back from Jamaica. Thus began the legend of Metro. He would soon become one of the very first sounds in England, playing at first in the Krays’ cave every week for five years and then travelling under the name Tune Waver. A school friend, cameraman for Metro Goldwyn-Mayer, convinced him to change his name to the somewhat more humble Metro the Tune Waver Downbeat. Only Metro would last. From dance to dance the crowds rushed in until the fight in 1967. Partially blinded, Metro retreated into engineering.

In 1969, Metro met a young man in a north London club who would become the best known representative of his engineering talents. The man’s name was Jah Shaka and for the future icon of the English roots scene Metro crafted one of his first amplifiers for non-personal use. “I did it in close collaboration with the guy who invented the tube I used in this particular model,” he recalls. This custom-made piece, with an unparalleled sound, would become an integral piece of Jah Shaka’s success, arousing spies, questions, and envy until the equipment was stolen a few years back while Shaka was away. “Since then I’ve done a new one for him using transistors but it’s not quite the same thing.” Today, Metro works a lot less. His favorite tube, the KT-88, has become rare and only one supplier can still find them for him in London at an exorbitant price. Once that supply disappears an entire line work could well become extinct.

Mark “Mostec” shows off one of his pre-amps

Despite the dire state of the industry, certain young disciples aren’t discouraged. Mark “Mostec” Skeete is among them. At 36, he has become in a few short years one of the best builders of pre-amps, which he calls, “The brains of the sound system.” In his Leyton hideout, components cover the floor and the walls. After having started with amps, “to prove to my brother that I was capable of building one,” Mostec moved to pre-amps. He didn’t expect it to become an all-encompassing pursuit, one that includes his sister, who helps him build. “I was supposed to make one for me, one for a friend, but the bodies were really expensive and the prices dropped if I ordered five. So I had another three to build,” he explains. Chance, or to be more exact his childhood friend Kenny Knotts, pointed him to a potential buyer in 2002, a Frenchman, Ras Abubakar, of the Zion Gates sound in Nantes. Since then, the quality of his work has brought famous names to his door, including Channel One and King Shiloh, culminating in the yearly rush around the Notting Hill carnival. “People who come from Europe for carnival use the occasion to pick up pre-amps,” Mostec says laughing. Each pre-amp he builds runs from 500 to 1,200 Euros. Expensive, but Mostec, like Metro or Shortman, doesn’t really make much of a profit. The materials are beyond expensive. Still that doesn’t discourage these hard-headed artisans. “I’ve sometimes thought about giving it all up,” confirms Shortman. “I lasted two months. Then I started again. It’s like an addiction. It is what it is. You love it or you loathe it.” No middle ground. Under his beanie, Shortman cracks a smile. “As long as god wants me to, I’ll continue.”

Mostec’s workshop in Layton, London.