Text: Rob Schenk

Japan has always had a deep love and appreciation for reggae music. From local dancehall nights to national tours with renowned artists, the history of reggae in Japan is nuanced and somewhat difficult to track, and the history of sound system culture is just as elusive. Ahead of Dub-Stuy’s upcoming debut in Osaka and Tokyo, Rob Schenk spoke with Riddim Chango founders, Kuranaka 1945 and Jeremy Freeman of Deadly Dragon Sound in order to learn more about this thriving scene.

Reggae is a global music. From its original Jamaican roots to the multitude of forms it now takes across the globe, reggae has become the universal voice of the oppressed. Its ideas of respect, revolution and living life to the fullest are universally appealing. But in some places, this cultural expression starts to transform, and Japan has been a unique hot spot for reggae and dancehall music.

1970s: Babylon By Bus

Although the first reggae band to tour in Japan were brothers Sydney and Derrick Crooks as The Pioneers, Bob Marley’s Babylon by Bus performances in 1979 were the fuse that ignited Japan’s reggae craze.

“Many of the older reggae fans I know in Japan speak of how Marley’s ‘rebel spirit’ captivated them during his first tour. His dreadlocks, his revolutionary thinking seemed in such opposition to the prevailing conformist culture of Japan at the time,” says Jeremy Freeman, veteran DJ and owner of Deadly Dragon Sound System who has been living and DJing in Japan for two years, based in Tokyo. “Later, in the 80s and 90s US Army bases (especially in Okinawa), had recently gained a number of West Indian soldiers due to the Army’s offer of US Citizenship to new recruits. These new soldiers brought all the new Jamaican sound system tapes with them, exposing sounds like Stone Love and Killimanjaro to a Japanese audience.”

While Bob Marley stirred it up on stages across the nation, another form of innovation was taking place; single stereo matrix loudspeakers, pioneered by the late Tetsuo Nagaoka.

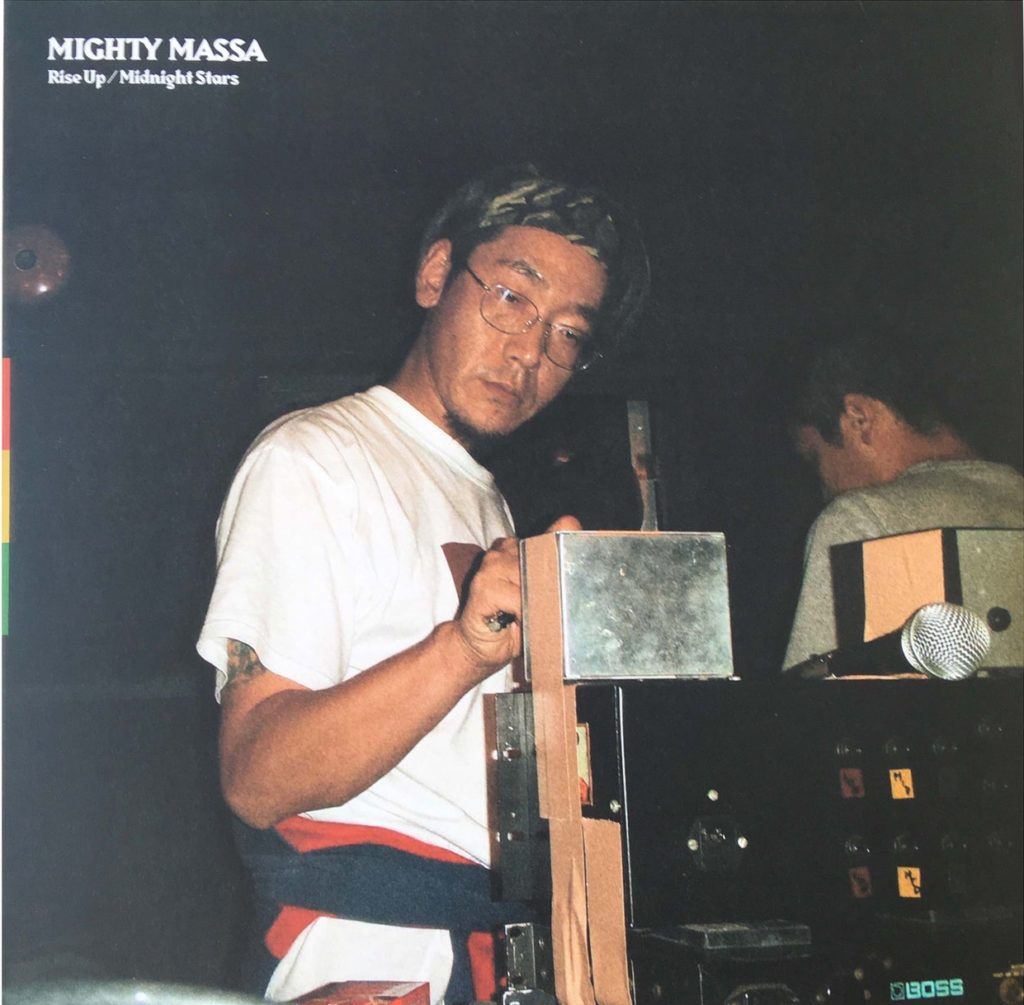

“Nagaoka influenced many other speaker builders, and the book he wrote on back loaded horn speakers was crucial for speaker builders at the time.” 1TA told me. 1TA and Hiroshi Takakura are the men behind Riddim Chango, a Japanese reggae and dub record label that has worked with the likes of Cornell Campbell and Macka-B, as well as the legendary Mighty Massa.

1980s: Dry & Heavy

With other Jamaican media such as The Harder They Come and Rockers finding releases in Japan as well, Jamaican culture was put in the spotlight. Coinciding with this rise in Jamaican popular culture came the first sound systems in the late 1980s, with Rankin’ Taxi leading the charge.

“Rankin’ Taxi built his sound system Taxi Hi Fi in 1984 and it’s largely considered the first reggae sound system in Japan,” 1TA said. “Mighty Massa founded his Mighty Massa Soundsystem in 1994, and that was the first UK style roots/dub sound system in Japan.”

With the systems rising up, live bands began to form as well. “Mute Beat, Dry&Heavy, and Audio Active are Japanese foundation artists,” Hiroshi began. “They used Jamaican reggae music as a platform but they also had a definite Japanese identity. Because we don’t have Caribbean musicians, the vibe and grooves are totally different from Jamaican reggae. Many reggae and dub bands in the early days were also influenced not only by reggae music but also jazz, hip-hop, etc. so the sounds of those bands are more diverse.”

This includes artists like the legendary percussionist Pecker and the group Fishmans, who were creating dub and roots music as early as 1981. The legendary Nahki started at this point as well. Although he organized the first “Japansplash” reggae festival in 1985, Nahki was also one of the earliest Japanese to travel to Jamaica, recording “Original Ninja” with Prince Jammy in 1989. He eventually went on to record with Tachyon, a New York and Japan based label affiliated with Bullwackies.

Though largely underground, reggae music and sound systems quickly garnered a following, with around 150 reported sound systems in the country. Systems like Mighty Massa paved the way for this movement, jumpstarting dancehall and sound system culture and an interest in reggae through their focus on dub. “Nobody can make music like him. He is the one and only Dubwise legend,” 1TA said of Mighty Massa. Hiroshi elaborated on Massa as well:

“He doesn’t use any plugins in his production. He still produces as 90s dub producers did using analog synths, drum machines and mixing desks. That’s why his tunes stand out from the others. Personally I really love how he mixes snare drums. The reverb, delay and feedback effects sound mad but are mixed so precise. I can feel the depth of dub music through him.”

1990s: Worldclash Champions

But some people needed more; traveling to Jamaica and New York, Japanese people went to the source and studied what they heard.

“Many young people started going to Jamaica, and started bringing dancehall and reggae sounds to not only major cities but also small cities all over the Japan,” 1TA said.

“This was due to the influence of the pioneer Rankin’ Taxi. I personally experienced dancehall sound systems for the first time in my home town around 1997, and was astonished by the loudness of the system! A club in Tokyo where I often DJed was using Mighty Massa Soundsystem as their in-house speakers, and it was normally tuned for all types of music, but when he put his music through a pre-amp, it sounded completely different and mashed up the place! A restaurant above the club had a fish tank and apparently the vibrations killed the fishes,” 1TA laughed.

As the movement progressed, Mighty Massa and other producers began to create their own versions of popular tunes, crafting custom dub plates and never-before-heard melodies that shook the floors of clubs everywhere. The culture became so popular that newspapers for the sound system and dancehall community were created, with publications like Strive and Riddim. This happened directly because of the Japanese love for reggae music.

“In Japan, there is a methodology to craftsmanship and study. It involves a lot of repetition and duplication of existing masterworks, and gradually by mastering the past something unique and individual evolves,” Freeman explained.

As sound systems began to spread and grow, they became more popular, and live music similarly picked up speed. With the advent of Mighty Crown Sound System’s 1999 World Sound Clash victory, Japan put itself on the map for reggae music but also for the blossoming sound system culture that was taking place. Systems like Fujiyama, Red Spider, Blast Star, King Jam, and Ryuganji Hi-Fi represent a wide swath of reggae styles and systems, from dancehall to ska and everything in-between.

“In Japan, people want proper sound systems; even small reggae bars have sound system stacks and they all sound great! Very unlike New York bars which will settle for a few JBLs” Freeman exclaimed.

The Japanization of reggae has also led to a burst of new talent, changing the forms of reggae music and orienting it from a more local, Japanese perspective. The ska wave that hit Japan in the mid 1990s was influential not just in classical ska but also in how it influenced the punk and rock music at the time, with bands such as Blue Beat Players and Coke Head Hipsters creating punchy, grungy versions and interpretations of traditional ska music.

2000s: Stadium Reggae

Through the 2000s, reggae and sound system culture became cemented into Japanese pop culture, and the popularity of dancehall rose as well; With Junko winning the Jamaica Dancehall Queen competition in 2002, the scene exploded, and led to hundreds of dancehall artists and dancers all over Japan, with acts like Moomin and Pushim regularly making the Top 40. Japan’s reggae fever culminated with Mighty Crown’s first Yokohama Reggae Sai in 2005. The 30,000 people festival, taking place in Yokahama’s Stadium became a must for the who’s who of the dancehall world.

In the shadow of dancehall’s popularity reaching stadium level, the UK dub and sound system scene was also growing in clubs which started to pop up all over the islands. Although some of them have since closed down, there are still some memorable spots.

“Not many venues in Japan want to do reggae nights and host sound systems anymore because of sound restrictions and noise complaints. It’s even gotten hard to have sound systems in outdoor spaces. But Daikanyama Unit where we host “Tokyo Dub Attack” supports sound system culture so much, and we can be super loud so Unit is my top favorite venue. As I said there are are only a few venues where we can put systems, so each one is very important.” 1TA said.

“In the Kansai area where I live,” Hiroshi began, “There used to be good sound system dances at Whoopees in Kyoto, Bayside Jenny in Osaka and many more, but most of them have closed their doors now. It’s hard to find venues where we can put sound systems and do all-night dances in Osaka, even harder than Tokyo. But we run a night called “Dub Meeting Osaka” at the venue Socore Factory and their speakers are heavy enough for our dub event. We also get a good amount of people every time and vibe is wicked. All we need is to keep going.”

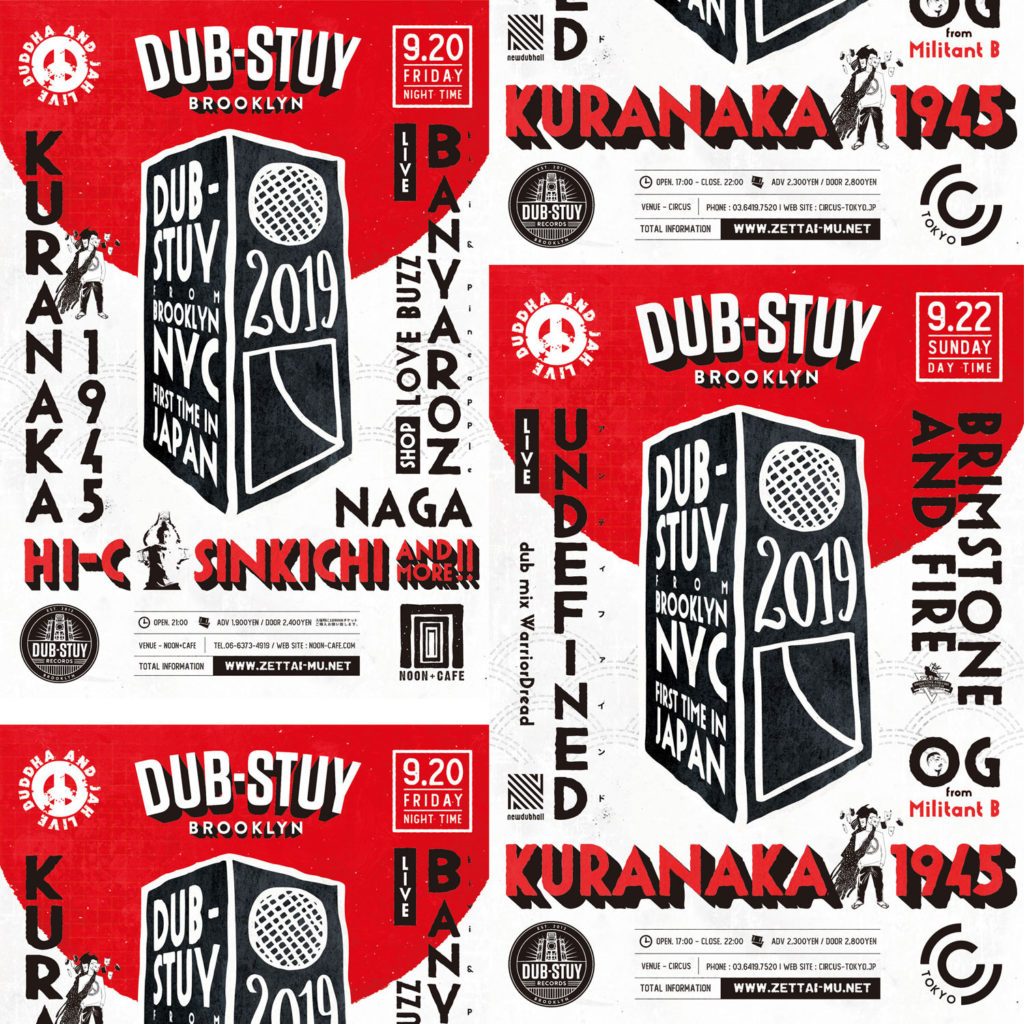

Historically LIQUIDROOM is known as one of the most popular venues, according to Kuranaka “Zettai-Mu”, a popular DJ and promoter. Known as Kuranaka 1945, he has organized over 500 shows and has played with the likes of Jah Shaka, Mad Professor and Zion Train.

“They had many great shows in the early days, and brought over Aba Shanti-I and Zion Train among others, who at that time weren’t well known in Japan yet. They’re pioneers, and I really respect them.”

2010s and Beyond: The Future

Today, modern roots labels such as Riddim Chango continue to collaborate and release new, modern Japanese-Jamaican dub and reggae. Other labels such as Overheat have been consistently releasing music since the 1980s.

“Some labels are doing great work,” Hiroshi said. “Newdubhall with Lucy and Sahara from Undefined have been releasing experimental dub tunes. They haven’t released a lot yet but they’ll definitely be putting out more cutting edge dub on vinyl, so it’s worth it to check them out. Dub Kazman in Osaka runs Rough Signal Records and has been putting out killer tracks. In terms of UK and European style dub music, I think Kazman is the top guy in Japan now. Cojie from Mighty Crown also runs a sound system and label called Scorcher Hi Fi. It can be considered a roots and dub version of Mighty Crown. The label has been dropping some deep sound system tunes.”

“Young 140 guys Karnage and Dayzero also run a label called Vomitspit; it’s a Dubstep label but they’re doing really great. Those four are my favorites. It’s not easy to keep a reggae record label going in Japan. The scene isn’t very big, the main market is in the UK and Europe and press factories are also in Europe, so we have postal and promotional issues. Not many people have time to check out new music or can’t afford to buy vinyl, so I respect these guys who bring this music forward in this difficult situation. They make me to want to work harder and release more music from Riddim Chango!”

But what of the future? With the rise in popularity of the dancehall and a downturn in roots reggae, some Japanese people might not know that dancehall originated Jamaica, as a 2002 Vibes article pointed out. And there seems to be a downturn in roots and ska-inspired creatives from Japan.

“We need more young talented MCs and producers to make the (reggae and roots) scene bigger, but I reckon those youngsters will come out soon,” Hiroshi said. His partner 1TA echoed him. “Like ramen and curry were brought from abroad but became completely different styles in Japan, I think Japanese reggae will become its own original form.”

Kuranaka also pointed out that promoting dub and reggae concerts isn’t always easy.

“I started playing dances about 25 years ago, in the ’90s,” Kuranaka said. “When I was teenager I went to see Jah Shaka and Aba Shanti-I and was jolted by their performances too. I started off by bringing some overseas artists and putting them on stage with Japanese artists. It was a simple idea, but it was a good way to get started. There aren’t a lot of specialized dub promoters here however. Most companies combine artists, promoters and labels together, and there are some people that only promote for one record shop or one local dance,” he said.

But the best part about reggae is that no matter where it goes, it always remains true to itself: a revolutionary sound and spirit designed to inspire love, seek equity, and unite people from all corners of the world. Although the culture is constantly changing, that spirit is alive and well in Japan. As 1TA puts it: “I love reggae because of its positive message and simple but ruff and tuff sound. I like the I&I way of thinking; reggae teaches us loads of things which we never learned in school.”

Kuranaka thought so too. “I think that the roots, the culture and the message put into this music is so important, and the gathering of people is good for the world. There’s so much love. I couldn’t have gotten where I am today without many friends, and I am thankful for the many sound systems, venues, crowds and crews that support us.”

And Hiroshi is right behind him. “I like having the heavy but pleasant bass and positive vibes flow through my body. The echo, delay, really any dub effect trips me out, so I have a mental and physical experience rather than just listening to the music. I think it’s good for everybody.”

Catch Dub-Stuy’s Japan debut on September 20th in Osaka and September 22nd in Tokyo. Promoted by Zettai-Mu. Click here for more information.

Research for this piece utilized information from the following resources:

Babylon East by Marvin D. Sterling; A History of MuteBeat by David Katz; The Rise of Dancehall in Japan by Kristal Roberts; Kodo Ejima: The Reggae Monk of Kyoto by David Katz; Tokyo After Dark by Baz Dreisinger; War Ina Tokyo by David Katz